Great Frontiers of Post-Modernism

This time, the special theme is Frontiers, inspired by a recent book-research trip out to California, a place referred to by some as the farthest place you can run from your problems without getting wet. The American West was once a very important frontier, but one that ceased to have as much relevance since the 70s. Americans ran there seeking fame and fortune starting the exact instant of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and did so again in 1849 for gold, and again in the 1920s to become movie stars, and again in the 1930s, flat-broke, to pick fruit for three cents a bushel, and again in the 1960s to "tune in, turn on and drop out." But since then, the American West has steadily receded as the place to either find or lose oneself.

For a long time, American writers chased another frontier, one with which we have an overdue reckoning, and that is Post-Modernism. For many years, we've been asking, If post-modernism is what comes after modernism, then what comes after post-modernism? Over time, it's gradually become clear that it's Nothing. Nothing comes after Post-Modernism, just as nothing comes after the Universe or Infinity or Time. But we all had high hopes for Post-Modernism, that it might be our theory of everything. Of course, we probably thought that about Modernism, too, when it was ushered in by Shakespeare in Hamlet (1600). Modernism has had a great run, in fact: four hundred years and counting.

But Post-Modernism, or the antidote to Modernism, also did very well for itself, and in fact one can sense its stirrings in another Shakespeare play, Taming of the Shrew, featuring a drunk, sleepy character named Sly, who the audience knows is really an actor in a Shakespeare play, playing a character in a Shakespeare play who believes he has awoken as an audience member at a different play, not the one he's actually in, and not the one Shakespeare's audience members have paid to see. It's a mind-bending moment for Shakespeare's audience, and for we readers of the play because three versions of reality, two of them utterly made-up, are crashing into each other.

After that, Post-Modernism mostly goes underground for about 250 years, finally cropping up again in Flaubert's Madame Bovary (1859) about a young narcissist named Emma Bovary who only cares about make-believe, and lives in a reality she keeps secret from most people, especially her husband and daughter who she neglects. Emma has no values, no beliefs. She just wants pleasure for herself and holds nothing else sacred. So she ignores all modern conventions of personal fidelity and social responsibility like a good post-modernist should and mayhem results.

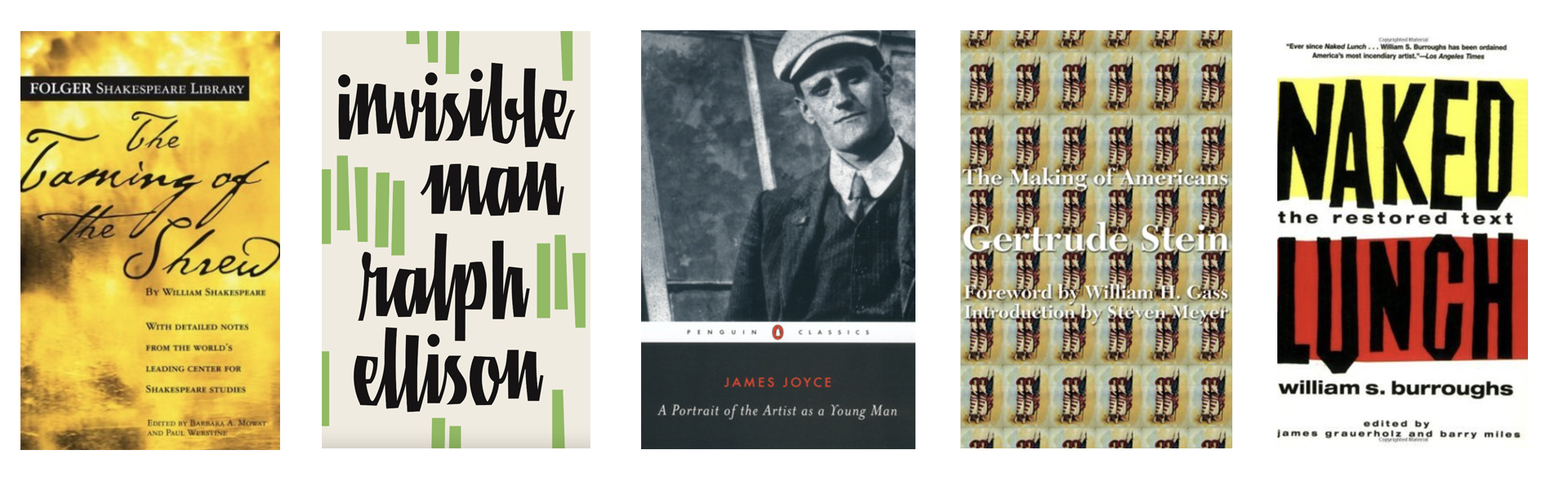

After Flaubert, Post-Modernism deep-dives again and doesn't truly resurface til after the Second World War in novels like Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man (1953) and William S. Burroughs Naked Lunch (1959) and Kurt Vonnegut Jr.'s Slaughterhouse Five (1969). (Though we can't discount Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) or Gertrude Stein's The Making of Americans (1925).) Once we arrive at Vonnegut, who went out of his way to show that his hero, Billy Pilgrim, was a crudely-fashioned Everyman, a symbol for all soldiers driven insane by war, propped up before real Nazi concentration camps, the game was really up for Modernism. In fact, it is amazing it has continued to this day. That is, technically speaking, once we writers stepped out from behind the curtain, and started fully showing our hands, there was nothing more to see.

Though truly big post-modern books and stories do still surface from time to time. A dandy was The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien (1990) in which O'Brien plays the deep game with Vietnam, a war in which even the body counts were not real.

From where will the next great innovation come? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you. Though if Vonnegut and O'Brien are any indication, it will come from someone so outraged by some horrific and impossible encounter with reality, they must invent some as-yet-unimagined smashup of reality and make-believe with enough originality and metaphorical force to shock us.

Which won't be easy, because we have now seen the eight-minute, forty-six-second tape of George Floyd's murder.

A post-modern movie that still deserves attention is Reds (1981) with Warren Beatty and Diane Keaton, which documents the attempt at a Socialist/Communist revolution in America in the 1930s. The post-modern part happens through the intercutting of interviews with surviving Americans -- actual pinkos and commies -- people who really suffered through the throes of a failed revolution.

For any new readers: My new novel, Tania the Revolutionary, is available on Amazon for Kindle and paperback or Barnes & Noble for eBook.